Back in spring 2020 at GoOut,

we were looking to replace our Spring-Tomcat

duo by a more lightweight framework to power our future Kotlin microservices.

We did some detailed (at times philosophical) theoretical comparisons that I much enjoyed,

but these cannot substitute a hands-on experience.

We decided to implement proof-of-concept microservices using the most viable frameworks,

stressing them in a benchmark along the way.

While Kotlin was the main language,

I saw this as an opportunity to have some fun at home and test (my proficiency with) Rust,

which is touted for being fast.

I ended up stress-testing Kotlin’s Http4k, Ktor,

and Rust’s Actix Web, read on to see how they fared.

Back in spring 2020 at GoOut,

we were looking to replace our Spring-Tomcat

duo by a more lightweight framework to power our future Kotlin microservices.

We did some detailed (at times philosophical) theoretical comparisons that I much enjoyed,

but these cannot substitute a hands-on experience.

We decided to implement proof-of-concept microservices using the most viable frameworks,

stressing them in a benchmark along the way.

While Kotlin was the main language,

I saw this as an opportunity to have some fun at home and test (my proficiency with) Rust,

which is touted for being fast.

I ended up stress-testing Kotlin’s Http4k, Ktor,

and Rust’s Actix Web, read on to see how they fared.

Feel free to jump to the results and read the background later, if you’re impatient.

On TechEmpower Framework Benchmarks

Why not just refer to excellent TechEmpower Benchmarks (TEB)?

A very valid question to ask. A couple of reasons:

- Submitted TEB implementations tend to be rather optimised. We wanted to measure such a code style that we would normally write: one striving to be simple/idiomatic/readable, but finished promptly and not extensively profiled. On the other hand, we wanted to include production-grade API error handling (correct HTTP codes and JSON error messages listing problems of individual parameters etc.), request logging, and OpenAPI (Swagger) spec generation.

- Besides high-water req/s performance and associated latencies, we wanted to capture more operational characteristics like memory usage, CPU usage and efficiency, along the lifetime of a microservice instance.

- In production, we run our microservices in a rather high-density Kubernetes cluster, where every instance has to be CPU- and memory-constrained. We wanted to simulate this environment and check whether we can use trending “serverless” offerings for new services.

- Our data store, Elasticsearch, differs from ones included in TEB, and we were curious how synchronous vs. asynchronous flavours of the Elasticsearch client compare.

The Service

For a description of the service to implement & benchmark, see its API Spec document available in the locations-rs repository.

We benchmark its simplest /city/v1/get endpoint,

whose work is to look up a city document by id in Elasticsearch,

look up associated region document,

and render response JSON.

It uses internal in-memory cache for regions (there is just tens of them),

but no cache for much more numerous cities.

To reduce bandwidth when fetching documents from Elasticsearch,

all implementations instruct it to strip (at least) the largest property geometry.

This property is only used in Elasticsearch-side filtering, not by the microservice.

I believe the stripping significantly strains Elasticsearch

(or rather transfers the strain from the microservice to it).

The Benchmark

Recipe

The benchmark consists of multiple identical “runs” for each Dockerised implementation spawned

by bench-3-impls.py.

The runs are named after the implementation and their ordinal number,

thus rs-actix-1 is the first run of the Rust (Actix) implementation,

and kt-ktor-3 is the third run of Kotlin (Ktor) implementation.

Each run simulates the first couple of minutes of the microservice instance using test-image.py. Steps of one run:

- Docker container is started, measuring the time until the service starts responding,

- a suite of HTTP checks is made ensuring correct responses and error handling behaviour,

- HTTP load is generated using wrk

in a series of 10-second long steps with increasing concurrent connection count;

the metrics are collected from

wrkand Docker API after each step:- first 5 steps use just one concurrent connection, acting as a warm-up,

- each of the next 11 steps doubles concurrent connection count, i.e. continuing with 2, 4, 8, …, 1024, 2048.1

Finally, all runs are plotted using the awesome Pygal library in render-tests.py. Different runs of a single implementation use the same colour, allowing for visual inspection of the variance between them.

Runtime Environment

Docker is told to constrain resources available to the microservice containers, a practice usual in typical Kubernetes clusters.

The CPU is limited to 1.5 CPU-units using an equivalent of the --cpus=1.5 Docker option.

This means that even though the instance has access to all 4 CPU cores of the machine,

it can use only 15 CPU-seconds (out of theoretical 40 CPU-seconds) in each 10-wall-clock-second step.

The value of 1.5 was chosen small enough to ensure the tested microservice is the actual bottle-neck during the benchmark,

and large enough to assert frameworks make proper use of multiple CPU cores.

Memory is limited to 512 MiB. I argue that anything beyond 512 MiB should not be called a microservice.

The two JVM-hosted Kotlin implementations run in OpenJDK 11,

with -XX:MaxRAMPercentage=75 as the sole option.

It should allow JVM to allocate up to 75% of available 512 MiB memory to Java heap.

Hardware

The benchmarks run on 2 Virtual Machines in Google Cloud Platform (GCP) Compute Engine located in the same zone.

- 1st VM,

n2d-highcpu-4machine type (4 AMD Epyc Rome vCPUs, 4 GB memory):- Runs the benchmarked microservice in a Docker container and the

wrkload generator. - As the container is limited to 1.5 CPU and

wrktakes less than leftover 2.5 CPUs, they should not affect each other. - Indeed, the maximum CPU utilisation during short peaks never exceeded 70%.

- The N2D machine type is said to have the best performance/cost ratio on GCP and even across cloud providers.

- Runs the benchmarked microservice in a Docker container and the

- 2nd VM,

e2-custommachine type (12 high-density vCPUs, 6 GB memory):- Runs a stock Dockerised Elasticsearch 7.8.0 instance, storage backend for the microservices.

- Maximum CPU utilisation during short peaks never exceeded 80% — I have scaled the number of Elasticsearch CPU cores up until it ceased to be a bottleneck, arriving at 12.

The Contenders

locations-kt-http4k: code on GitLablocations-kt-ktor: code on GitLab.- lang: Kotlin v1.3.70

- framework: Ktor v3.163.0 with Netty server engine v4.1.44

- programming model: async (Kotlin coroutines)

locations-rs: code on GitHub.

We also initially implemented a Kotlin proof-of-concept in Vert.x, but it turned out none of the team members was keen on the programming paradigm this framework suggested (which may be a subjective matter), so we hadn’t proceeded further with it.

The Story of locations-kt-http4k

Http4k Locations service was written by @goodhoko at GoOut. It became the production implementation at GoOut and is thus most complete along with extras like Swagger serving.

Http4k allows one to select from several server backends, so we first need to do a qualification benchmark and select the best performing engine to be fair.

See Kttp4k server engine results on a dedicated page. Line labels on the graph correspond to tags in the locations-kt-http4k repository.

One nice side-effect of this benchmarking was that

I have discovered a cause

of the Netty backend performance issue,

and @daviddenton was quick to fix it.

The netty-updfix-* graphs, which exhibit some nice latency characteristics, already contain the fix.

It was later released in http4k v3.259.0 (be sure to upgrade if you use this backend).

Apache HttpCore version 4.4, labelled as apache4-*, was most CPU-efficient backend

and achieved shared first place in peak req/s performance.

However, it tends to draw too much memory as the number of concurrent connections grows,

and is out-of-memory-killed once their number reaches (extreme) 1024.

Apache HttpCore version 5.0 (apache-*) and a variant with lowered socket backlog (apache-q100-*)

suffer from the same problem.

I have opened an issue to see if that’s a bug or not,

insights welcome.

Meanwhile, I would recommend different http4k backends for services not shielded by load balancers.

The winner of this qualification round is the Undertow backend

(undertow-* for v3.163.0 and undertow-upd-* for v3.258.0),

which shares the first place in high-water req/s performance,

but also brings good all-round results in the rest of the metrics,

especially memory consumption under load.

The Jetty backend (jetty-*) slightly but consistently lags behind other production engines

in most metrics.

For completeness, I have also included the SunHttp backend that is intended for development only,

which the benchmarks confirm.

Update: Http4k author has pointed out that OpenAPI generation through Contracts API may incur some performance penalty. Benchmarks confirm that removing the Contracts layer indeed increases performance, shifting Http4k closer to Ktor. Graphs below reflect the original version with Contracts (OpenAPI support).

The Story of locations-kt-ktor

Ktor variant was also written by @goodhoko at GoOut,

I later tweaked the /city/v1/get endpoint for functional parity with other implementations.

It remains the least complete implementation with just this single endpoint.

It uses es-kotlin-wrapper-client to wrap intrinsic async API of the Elasticsearch client into Kotlin coroutines.

Ktor also allows for pluggable HTTP server engines which I benchmarked. See Ktor server engine benchmarks page.

The pattern is similar here with Netty being more efficient and performant than Jetty, thus qualified as Ktor’s engine of choice for the main benchmark.

The story of locations-rs

I wrote the Rust clone in my free time, closely following the development of locations-kt-http4k.

As Actix Web 3.0 was just released and I was eager to compare how it fares against v2.0 performance-wise. The one-to-one benchmark shows v3.0 is at least on par with v2.0. I think that’s good news given that v3.0 has advanced on the safety front. Note that I had to remove Swagger support as paperclip is not yet ported to Actix 3.0, but that should have no runtime effect. The rest of this article uses the original actix-web 2.0 version, but we know the conclusions apply equally well to the newest v3.0.

The benchmarked build employs cheap performance tricks. Do they make a difference? Yes they do, the dedicated Rust optimizations benchmark page shows that:

- Putting

lto = "fat",codegen-units = 1into[profile.release]section ofCargo.tomlincreases performance by ~17% and efficiency by ~19% over a plain release build (labelledrs-actix-base-*). - Adding

RUSTFLAGS="-C target-cpu=skylake"orRUSTFLAGS="-C target-cpu=znver2"3 on top didn’t affect the results. It may be that this workload does not benefit from any SIMD instructions beyond base x86-64 ones and/or they are runtime-detected and used even when not supported by target CPU. Elfx86exts detects SS(S)E3, AVX(2) instructions even in the base build.

Another contributor to Rust efficiency was perfectly timed

@seanmonstar’s change to the num_cpus crate to detect soft CPU limits used by Docker.4

All major async runtimes and thread pools depend on num_cpus

to spawn the most efficient number of worker threads.

In Actix this is amplified by the fact that it

launches a separate executor per each logical CPU.

Given the soft CPU limit of 1.5 cores, the change decreased worker count from 4 to 2.

Finally a piece of trivia: Being unaware of incompatibilities between some Rust async runtimes, I had originally used the Tide web framework built on top of async-std. Problems arose as soon as I plugged in elasticsearch-rs, which uses Reqwest HTTP client which in turn depends on Tokio. I went as far as crudely transplanting Reqwest for Surf in elasticsearch-rs. While it worked, it was not sustainable and I missed some bits in Tide’s error handling API. Luckily enough, porting to Actix involved mainly just redoing the said error handling.

The Results

All graphs below are interactive infinitely scalable SVGs.

If you’re a Firefox user, you can Open Frame in New Tab (available in the context menu) to see them in full.

The startup time is measured from the moment Docker finishes setting up the container

to the moment when we receive a valid HTTP response to GET /.

The services are required not to start if configured Elasticsearch server is unreachable,

i.e. required to do an HTTP round-trip to it.

Both JVM-based Kotlin services start well under 3 seconds, which is impressive given the JVM has to load itself, the service 40+ MiB fat JAR and perform initialisation.

Actix’s Rusty startup times are barely visible in the graph as they take 1–2 ms, basically the time it takes to HTTP-ping Elasticsearch. Such single-digit millisecond startups allow for deploying on platforms like Google Cloud Run, which aggressively scale instances down to zero and may start them only after receiving a request.

In the Java world, technologies like GraalVM may overcome the JVM limitation eventually.

Errors should be recorded in any benchmark, so here we go. All frameworks behave exemplarily in our case, giving pure zero errors till 512 connections, negligible errors for 1024 parallel connections, and around 3% (Kotlin) or 1% (Rust) error ratio for 2048 parallel connections.

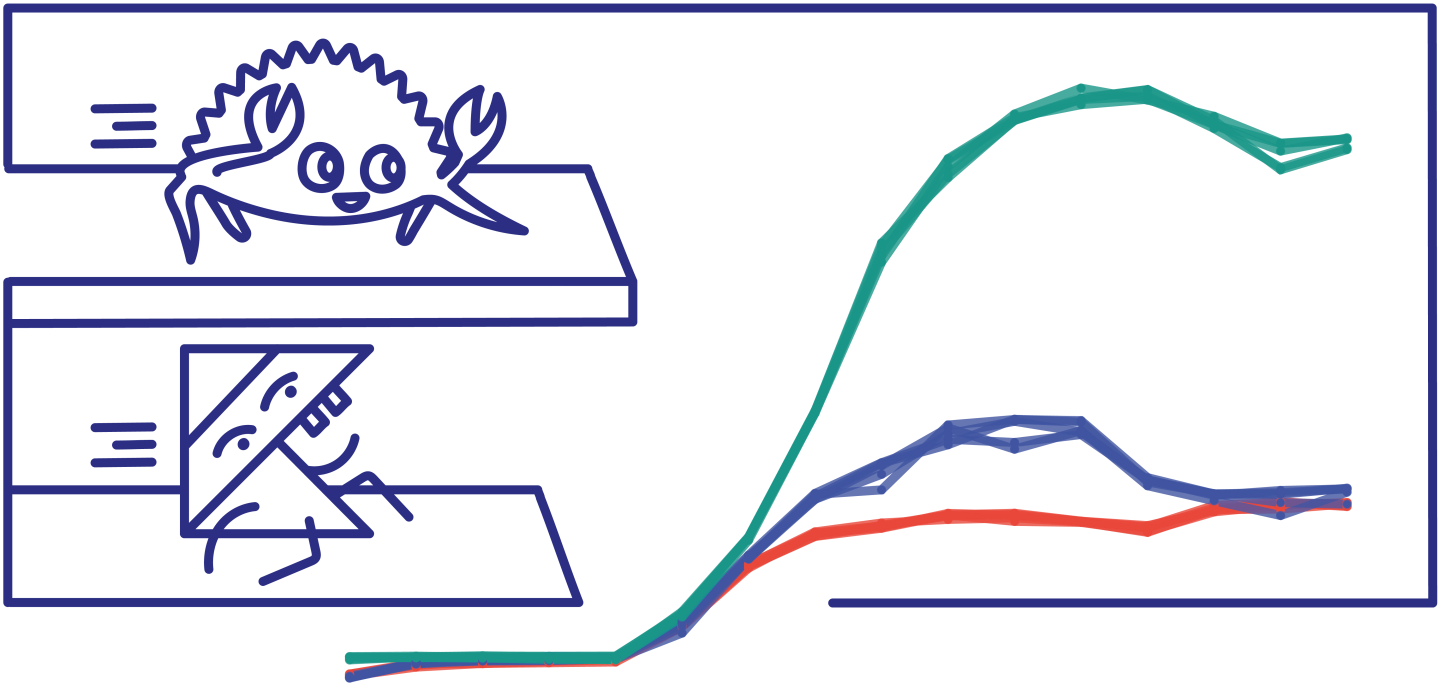

High-water mark successful requests per second as the number of concurrent connections grows, one of our main metrics. Let’s look at the results from left to right, as instance lifetime progresses.

- A couple of initial 1-connection warm-up steps show how JVM-based Kotlin frameworks gradually gain performance as they are being JIT-optimised (more on that below), eventually reaching temporary performance parity with the Rust implementation.

- Up till 4 connections, all implementations are bound by latency to Elasticsearch instance, yielding similar throughputs.

- At 8 connections Ktor and Http4k become CPU-bound, Ktor slightly higher up benefiting from its better CPU efficiency. Actix skyrockets.

- Http4k plateaus first, staying within 3000–3200 req/s range between 8 and 256 concurrent connections.

- Ktor reaches ~5000 req/s in the 32–128 connections zone.

- Actix hits more than double of that, ~11000 req/s for 128 and 256 concurrent connections.

- After reaching their peaks, both Actix and Ktor become oversaturated, showing slightly degraded performance. This effect is more pronounced and happens earlier in the Ktor case.

- The behaviour of Http4k in extreme connection counts is opposite, reaching its peak successful req/s of ~3500, despite the presence of non-zero error ratio. This stems from both increased efficiency and, to a lesser extent, exceeding Docker CPU limits. More on these later.

Coincidence or not, Actix & Ktor that share somewhat similar shapes in the graph are both based on async executors and low thread counts, while Http4k with slightly different pattern uses more conventional high thread count and blocking I/O.

Note that Google Cloud Run’s default (and maximum) concurrent connection count of 80 almost exactly hits the sweet spot of all measured implementations.

50th, 90th and 99th percentile latencies plotted using a logarithmic scale.

As expected, the latency story is an inverse of throughput, with 99th percentile being noisiest and showing anomalies in some Rust runs. The biggest (geometric) difference is in the 8–16 connections range where Kotlin frameworks already saturate available CPU, but Rust does not, yet.

The latency “cutoff” at the very right of the graph corresponds with the change of mode: from saturation-induced latency to appearance of error responses.

Here we measure high-water mark memory usage of the container from its start till the end of each benchmark step, as reported by Docker (i.e. not just momentary memory usage).

The comparison between JVM-based and Rust frameworks is not representative here as allocated Java heap depends on configuration in addition to actual usage.

The same metric as above, but divided by the number of successful requests per second; which gives an unconventional unit of megabyte-seconds per request.

It is normal that the values for low connections counts are higher because the base memory footprint of each framework is spread out across fewer requests.

You may notice a slight difference in shape between Http4k and the 2 async frameworks: Http4k gets down to ~0.05 MiB⋅s and stays there, while Ktor and especially Actix go up again as latencies increase. Caused by the async programming model or not? Share your thoughts in the discussion.

Consumed CPU time as reported by Docker API.

JVM is seen working hard to JIT-optimise Kotlin-based codebases during the warm-up steps. The just-in-time optimisation, combined with the execution of unoptimised code, takes roughly 23 CPU-seconds extra, a remarkably small amount of resources.5

Still, this is something to keep in mind about JVM-based microservices when considering, for example, high-frequency continuous deployment or aggressive instance count autoscaling. The JIT may also compete for resources with the not-yet-optimised target workload. Such characteristic should also apply to other JIT-based engines like Node.js’ V8.

Once we get to 2–8 connections and beyond, Kotlin implementations quickly saturate the allocated CPU portion, Rust following ~2 steps later.

Further right, Http4k manages to consume a bit more CPU than the 15 CPU-seconds assigned by Docker. That may contribute to its increase of requests per second in that region, but the ~3.5% CPU limit surpass alone does not fully explain a ~6% boost in performance.

Consumed CPU time divided by the number of successful requests per second, or CPU efficiency. Let’s divide the graph into two halves.

In the first half that spans from 1 to roughly 32 concurrent connections:

- The Efficiency of Http4k, Ktor increases rapidly due to JIT and because bookkeeping jobs like garbage collection get diluted between more performed requests.

- It is hard for me to explain the efficiency growth of Actix, which is more notable in an Actix-only graph. Is there some constant overhead of the async task executor? When idle, Actix consumes zero CPU cycles.

In the second half ranging from 32 to 2048 connections:

- Http4k’s efficiency increases slightly, which is all but expected in the overdose of connections.

- Ktor behaves as anticipated, showing reduction of efficiency.

- The very subtle efficiency decrease of Actix is responsible for the drop of ~1000 requests per second due to their inverse relationship.

My favourite metric at the very end; the running total of successfully served requests (time-integrated throughput) over the cumulative sum of used CPU time, or bang for the buck for short. Going up means serving requests, while going right means consuming CPU. Line slope corresponds to CPU efficiency.

If we take the furthest point of each implementation and divide the total processor time consumed by the total served request count, we arrive at weighted average CPU time per request, which incorporates CPU time needed to start the service and get it up to speed.

If we allow ourselves a blatant simplification, we can transform the number to more comprehensible cost per billion requests, assuming an example price $0.0275 per vCPU⋅hour and unrealistic perfect resource utilization.

| Http4k | Ktor | Actix | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU time per request | 560 µs | 460 µs | 170 µs |

| Cost per billion requests | $4.3 | $3.5 | $1.3 |

Please take these numbers with a grain of salt. Because benchmarked instances run only for a couple of minutes, we give excessive weight to startup costs. This effect may be only partially compensated by the fact that real microservices would probably run under a load much below their saturation points, thus taking much longer to serve an equal number of requests.

As pointed out by David Denton, the takeaway is that the cost of operating the microservice alone is incredibly low, and will be easily dominated by the development and other runtime costs.

Conclusion

In this post, I wanted to go beyond usual benchmarks by having an extended set of metrics to show more nuances of tested technologies and discuss some of their implications. I desired to compare each framework in its best shape, so I ended up doing 3 qualification benchmarks, which may hopefully serve people also on their own. All implementations, tools and data are open-sourced, so the benchmarks should be in theory reproducible by anybody; also it should be easy to add new implementations to the mix.

The post was only about runtime characteristics, which is just one of many aspects of each technology. Comparing developer experience would be material for a whole new write-up!

I want to thank GoOut for open-sourcing the 2 Kotlin implementations. Thanks go also to my former colleagues there for nudging me to write this up and for thoroughly reviewing a draft of this post. All questions, corrections, thoughts are of course welcome in any of the discussion channels linked below.

Updated on 2020-09-14 with some clarifications, and on 2020-09-16 with additional Http4k “contractless” benchmark. See post history in git.

-

The top-end concurrent connection counts of 1024 and 2048 are too high to be practical. They are included to test framework behaviour under uncontrolled traffic spike. ↩

-

A newer http4k version 3.258.0 with Undertow 2.1.3 very slightly regressed in performance, see http4k server engine benchmarks. ↩

-

The benchmarked microservice runs on AMD Epyc Rome processors of the Zen 2 microarchitecture, and should thus benefit from compilation with

target-cpu=znver2. ↩ -

The change was inspired by similar code in OpenJDK already present in OpenJDK 11, so we are making a fair comparison in our benchmarks. ↩

-

It is tempting to make an unfair comparison to Rust, where optimised build adds 17 CPU-minutes on top of 11.5 CPU-minute debug build. We should also acknowledge the artificially low amount of actually executed Kotlin application code in our benchmark. ↩